No security technique is perfect, but some are better than others.

Using any form of two-factor authentication is absolutely more secure than using none at all.

But it’s important to understand that nothing is perfect. Security is never absolute. There are ways to hack every form of two-factor authentication; some just are more difficult to hack than others.

Let’s review the options.

The risks of a two-factor hack

Even considering potential vulnerabilities, two-factor authentication (2FA) greatly increases your security compared to not using it at all. Various forms of 2FA exist, from SMS to authenticator apps and hardware keys. Each has its risks, but any significantly increases your account security. Enable 2FA wherever possible.

Least secure: no two-factor at all

If you’re not using any form of two-factor authentication on your important accounts that support it, you’re at the least secure level. All a hacker needs is your username and password and they can compromise or take over your account.

Naturally, I recommend making sure you’re using proper internet hygiene, including long, strong passwords, using a password vault, and never re-using passwords.

But I also recommend enabling two-factor authentication when possible.

Protect yourself: Enable two-factor authentication.

The next question is which two-factor technique to use. Let’s look at text messaging, authenticator apps, and hardware keys.

Help keep it going by becoming a Patron.

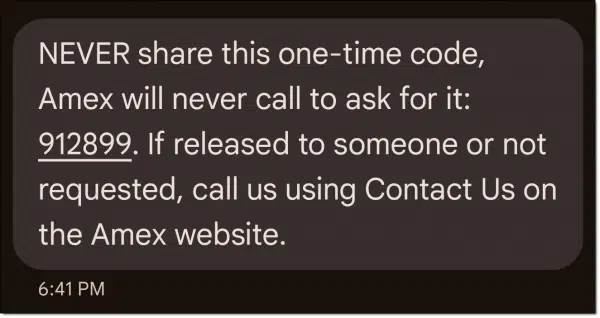

Good: SMS Text Messaging

When you set up 2FA for an account and then sign in1 to it, an SMS text message is sent to the phone number registered with the account. Your ability to enter the code provided in that text message proves you are in possession of your second factor: your phone.

SMS two-factor can be compromised in2 four ways.

- SIM swapping. Using this approach, a hacker convinces your mobile carrier that they are you. They have your phone number directed away from your phone and to theirs instead. They then receive the text message, not you, and gain access to your account.

- Physical theft. If someone steals your phone, they may be able to get your text messages, even if the phone is locked, depending on how you’ve set up security on the phone.

- Phishing. You click on a phishing link that takes you to a fake page looking exactly like one of the services you use. You sign in with your username and password, handing that information to the hacker. In real time, the hacker quickly signs in to the real service as you. They are presented with the real two-factor request, and a code is sent to your phone. They then present you with a fake two-factor request. You type in the code you got via SMS, thus giving it to the hacker, which they use to complete the sign-in on their end.

- Telephone company breach. I include this for completeness, but I think I’ve only heard of this once, and not with an established telco. A hacker gets into a telephone company’s system and redirects all your text messages to their phone without needing a number change or reassignment.

All of these present a barrier to hackers. SIM swapping might be the most common. Since all of these require time and investment on the part of the hacker, they’re really only a threat if you are worth targeting for some reason.

Protect yourself

- Check with your mobile provider; many have options to further secure your account from unauthorized changes.

- Keep your phone physically as well as digitally secure.

- Know what to look for to avoid phishing.

- I know of no way to protect yourself if your telco gets compromised, but I don’t consider it a real risk.

Important: the two-factor code is useless unless the hacker also knows your account user ID and password. This is true for all of the following scenarios.

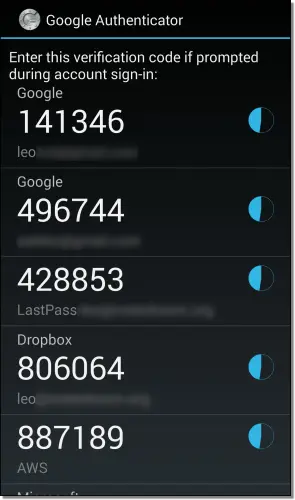

Better: Authenticator apps

When you use an authenticator app as your second factor, when you sign in you are prompted to enter a code currently displayed by an authenticator app running on your smartphone. When this is set up initially, the app and the service are linked so that only the app can provide the code the service expects. Your ability to provide the correct code proves you are in possession of your second factor: your phone.

Authenticator apps can be compromised in few ways.

- Phishing. You click on a phishing link that takes you to a fake page looking exactly like one of the services you use. You sign in with your username and password, handing that information to the hacker. In real time, the hacker quickly signs in to the real service as you. They are presented with the real two-factor request. They then present you with a fake two-factor request. You type in the code currently displayed on your authenticator app, giving it to the hacker, which they use to complete the sign-in on their end.

- Physical theft. If someone steals your phone and can unlock it, they can access the authenticator app and view the currently displayed code.

- Authenticator account theft. Several authentication apps allow you to synchronize their codes across multiple devices. For example, you might have it set to display the same codes on two different phones (yourself and your spouse’s, perhaps). That implies there’s an account associated with that particular authentication app and a way to transfer your codes to additional devices by signing in appropriately. If that process is compromised somehow, a hacker could install the same app on their device and get access to your codes.

I’ve never heard of authenticator-account theft actually happening. Installation on an additional device typically requires confirmation from one of the other devices in your possession, which you would then deny.

Protect yourself

- Know what to look for to avoid phishing.

- Keep your phone physically and digitally secure.

- Properly secure your authenticator account if you’re using one.

Much better: Hardware key

A hardware key is a 2FA physical device that provides access to accounts. When you sign in, you are prompted to insert a hardware authentication device into a USB port. (NFC, a wireless technology, can sometimes be used as well.) When you touch the device, or a button on it, information is provided by the device that proves you are in possession of your second factor: that hardware key. Much like the authenticator app, when you set up this type of two-factor authentication, you establish a relationship between the service and the key, after which only that specific key can prove it is present.

Hardware keys have only one vulnerability that I’m aware of:

- Physical theft. If someone steals your hardware key, they can provide it when requested when signing in to your account. You’d have to be targeted specifically for this to be an actual risk.

Protect yourself

- Keep your key secure.

The best: Hardware key plus you

In this 2FA technique, when you sign in you are prompted to insert a hardware authentication device as described above. In this case, the key also validates your fingerprint before activating. This then proves you are in possession of your second factor: that hardware key. As before, when you set up this type of two-factor authentication, you establish a relationship between the service, the key, and your fingerprint3, after which only that key plus your fingerprint proves it is present.

There may be one vulnerability:

- Physical theft + fingerprint spoofing. If someone steals your hardware key and has an image of your fingerprint, and the hardware key can be fooled with something other than your actual finger, they can provide it when requested when signing in to your account.

My take is that’s a level of barrier that’s only overcome in spy movies.

This is actually three-factor authentication. To sign in, you need:

- Your username and password. (“What you know”, in security parlance.)

- Your hardware key. (“What you have.”)

- Your finger. (“What you are.”)

Honorable(?) mention: you

I haven’t run into this in a true two-factor option for any of the services I’ve encountered, but if you look at the three-factor list above, you might think that there’s a second approach to two-factor:

- Your username and password.

- Your finger or face.

In other words, in theory, biometrics could be used as a second factor.

My guess is that common biometric identification — face or finger recognition on your phone or laptop, for example — isn’t quite as robust as that built into a purpose-built hardware key. The risk of false positives allowing the wrong people in might be too high.

Or perhaps it’s out there and I haven’t encountered it. I’m sure someone will let me know.

Do this

Use two-factor authentication. For most folks, it doesn’t matter which. Use whichever technique feels appropriate or possible for you and is provided by the services you use.

Consider using more secure forms of 2FA for your most important account(s), which is usually your primary email account since password resets and recovery codes are often sent there from the other accounts you have. I know some who take the position that this account warrants only a hardware key, though I’m not quite that adamant. It’s more important that you use the most secure form of 2FA you’re comfortable with.

I cover security frequently. Subscribe to Confident Computing! Less frustration and more confidence, solutions, answers, and tips in your inbox every week.

Podcast audio

Footnotes & References

1: Typically, only the first time, or after some period of time. Once two-factor has been passed, it’s generally not required again.

2: OK, “at least” four ways. I can’t claim to have discovered all possible compromises, but these appear to be the most commonly discussed.

3: It’s unclear if the fingerprint information is somehow stored on the key and validated or somehow passed on to the service for validation. I’m not sure it matters.

For websites that don’t support hardware keys, Yubico has an authenticator app on the Microsoft Store that works with a Yubikey.

Users can set up the authenticator app on a website by inserting the Yubikey and then scanning a QR code or copying the accompanying text code into the entry for that website.

I have a text file containing the authenticator codes which allows me to setup more than one Yubikey to work with the authenticator.

When a site asks for a TOTP code, I open the app, insert the Yubikey and copy/paste the resulting code.

There is also an Yubico app in the Google Playstore for Android phones that works with NFC capable phones and NFC Yubikeys.

This combines the protection of a dedicated authenticator app and a hardware key.

My wife and I share access to email and other data stored in the cloud, but we do so from different computers and cell phones. Messages to our cell phones as part of 2FA don’t work for us unless the message is sent to both cell phones, but I don’t see a way to set that up. Security dongles don’t work with our phones, and don’t work with multiple computers conveneniently. Email checks can work, but often, it seems the email messages don’t arrive within a convenient time frame. Sometimes, they end up in our email server’s spam filter, which takes time to find and untangle. Sometimes, they don’t arrive at all. We haven’t found a robust way to employ 2FA.

Google Authenticator compatible (i.e. the QR code thing) works well across multiple devices and across multiple users if needed.

“never re-using password” is the most important. If you reuse passwords, a hacker that hacks one account has access to all your accounts that use that same email address password combination.

If you use a different password on each, the hacker can only access one account.

Another Reason NOT to Reuse Passwords

Agreed Mark. I often read some folks opinion that different passwords are unnecessary … so wrong.

I would add using different user names and if the entity requires that your email address be your user name, throwaway email addresses are available to a lot of folk. Then each account has a different user name even if it is an email address.

Am I correct in thinking that makes your other accounts more secure should one be hacked? Either locally with you, or with the entity.

And don’t get me started on secret answers to questions! It is my favorite peeve that folk use info easily found in their online profiles.

I found that a huge disadvantage with a hardware security key is that you must be fanatical about having access to that key.

With three smartphones and a dozen different computers in a half dozen physical locations, I found that extremely inconvenient. There were many times, when, not only did I not have the key with me, I wasn’t 100% sure where it was!

There was also the issue of literally losing it forever and ensuring (in advance!) I had a way out (in?) if (when) that happened!

Short of having this thing on a retractable lanyard around my neck or tie wrapped(!) to my primary phone, this was not a reasonable situation. I quickly backed out of that approach.

Meanwhile, the perils of SMS for 2FA are way overblown by a lot of writers. In practice, it along with biometric locking, ends up being plenty “good enough” for the majority of my clients.

Except… one who is too old and confused to use an SMS capable phone! Given the number of accounts that require an SMS capable phone, I’ve had to use one of mine and make sure she can call me (on her landline) when a code is needed.

I was briefly able to use SMS to a Google Voice phone number for this client but, unsurprisingly, VOIP numbers in general are increasingly not allowed – for obvious reasons.

“And don’t get me started on secret answers to questions! It is my favorite peeve that folk use info easily found in their online profiles.”

Really?

Who would ever include their grade 3 teacher’s name in their own profile? Or even their own mother’s middle name, for example?

Also, I think you hit on a key element of all security requirements, Leo: anyone who thinks they are at risk of some exotic “digital security attack” had better have waaaay more than a couple of hundred bucks in their savings account! I think more than a few folks get “caught up” in the James Bond factor of securing their Joe Schmoe assets.

Password managers are great for sites that want secret answers to standard questions. The answers can be added as a note to the pass card for that site. And I’ve found that the answers don’t have to make sense to the question.

In fact, I’ve had to add the answers as a note because even I can’t remember what I answered:)

Some of us with time on our hands play around with these security methods to learn how they function more than out of fear of getting hacked. Although a security breach on some website can be a pain.

Someone once filed my Federal tax return for me in the hope of intercepting my tax refund. The IRS caught it before any damage was done, but one doesn’t have to have a large bank account to get hurt.

Having little money in your bank account won’t stop hackers. The most common hack is phishing. It masquerades as a real bank, and when you try to log in, they get your email and password. Second factor authentication would stop the hacker as they don’t have that key, app, or phone number. In most cases of phishing, SMS auhentication is fine. The phisher wouldn’t know who you are in that case.

I always answer the security questions with a lie or a phrase like “How the hell should I know?” And there are usually three or four questions. You can use the same lie for all of the questions.

And if the option exists to received the 2FA code via voice I choose that over a text.

I used the Yubikey with the Yubico authenticator app like Mark but it became too much of a hassle to always have the key with me so I switched to getting codes from Bitwarden.

I’m a “belt and suspenders” type when it comes to account security. In other words, I’ve set up multiple ways to get into my online accounts. The Yubikey is for my main ones.

I’ve found that most websites that allow the use of an authenticator app also provide for adding another for backup purposes. I also use Bitwarden’s authenticator feature for some accounts and the Microsoft Authenticator for some others. The Yubikey is needed to sign into Bitwarden, the way I’ve set it up it is the only way to sign in.

Also, I have multiple Yubikeys, including a couple of USB-C keys, one of which is almost always plugged in to the laptop or desktop PC which I’m using. Another is a USB-A that is also NFC capable that stays on the key ring with my car and house keys. Hardware keys such as the Yubikey and others are so uncommon that most people don’t recognize one for what it is. At least that has been my experience.

I’ll concede that Yubikeys aren’t cheap but they are near indestructible. And it is a pain setting up multiple keys to be used for each account. But it is essentially a one and done exercise. I definitely advise anyone who uses them to have more than one in the event one is lost. Account recovery methods for sites that a key is used for can be an ordeal if not set up beforehand.

Grade 3 teacher’s name, probably not. However, I’ve also seen poorly considered security questions, like “What is your favorite restaurant?” Not only something that is probably discussed online, but also might change over the course of a few years.

A multi-lingual friend of mine has the best solution I’ve ever heard of: She translates the last word of the question into her other language, and that is her answer. I suspect she will never be hacked.

My favorite restaurant is The Restaurant at the End of the Universe. I’ll neve use that in case the hacker is a Douglas Adams fan.

If someone steals your Samsung Android phone, but you have it PIN protected, wouldn’t your PIN keep them from accessing and using the phone?

Yes, but it woudn’t prevent someone pretending to be you from getting a SIM card with your number. That’s SIM swapping. Only the original DIM card is password protected.

2FA should offer to use transmission on other than SMS so one can take advantage of Face Recognition on apps like WhatsApp which also offer end to end engryption.

I’d like to see some mention / discussion of passkeys in this article.

Leo –

Regarding which two-factor technique to use, is receiving a voice message with the code on a landline phone better/safer than receiving a text message with the code on a mobile phone?

Thanks.

A land line is also subject to hacking, probably a little less than an SMS text, but most services don’t support a voice call.