It can be as secure — perhaps even more secure — because it’s used in a different way.

You can also choose to increase its security by using some of the same techniques we use for passwords in general.

The big difference: scope

The biggest difference between using a PIN and a password to sign in is that the PIN only works on the machine on which you set it up.

If someone knows your PIN, they’ll have access to your machine, but only if they also have the machine in their possession. If they can do that, your machine isn’t physically secure. With or without your PIN, anyone who has physical access to your machine can use any number of techniques to get at its contents.

There are at least two instances in which having an “easy” or even automatic sign-in puts you at additional risk:

- if you have saved logins or passwords in your browser — anyone can walk up to your machine and access those sites or credentials

- if you use Bitlocker to encrypt your data; logging allows access to that data

In those cases, the ability to log in — using that “easy to remember” PIN — could allow access, but it still requires physical access to the machine.

A PIN can be more secure

Many people fear a type of malware known as a keylogger.

When installed, keyloggers secretly record your keystrokes and send the recording to hackers. Log in to a website, for example, and the keystroke logger records both your username and password. Only something like multi-factor authentication can save you.

If you use a PIN to sign in to your machine, however, they can record anything they like and it won’t get them anywhere. The PIN only works on your actual machine, which some remote hacker doesn’t have access to. Even if you use a Microsoft account to sign in to your machine, that PIN is useless everywhere else.

There’s an argument that using a PIN is actually more secure, since you never actually type your Microsoft account password into your machine. Keyloggers can’t log what you never enter.

Help keep it going by becoming a Patron.

Strength: treat it like a password

If a PIN still makes you uncomfortable, consider treating it like a password.

There are two ways.

The first is to make it longer. There’s nothing that says you have to use your 4-digit ATM PIN as your Windows sign-in PIN. Use something longer — much longer, if you like. Just as adding a character to your regular password makes it exponentially stronger, the same applies to your PIN. Just add digits.

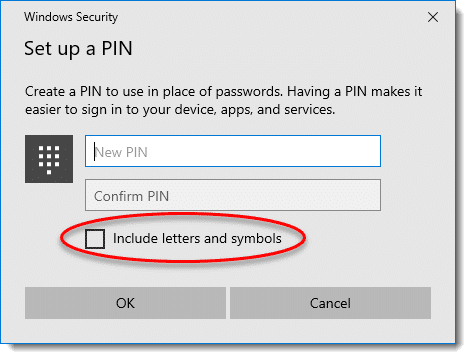

Speaking of passwords, the second is to include letters and symbols in your PIN.

A PIN with letters and symbols is nothing more than a password. This, then, would act as a alternative password used to sign in only to this specific machine.

Local accounts: PINs are convenient

Using a PIN is, I believe, intended as a way to make signing in to your Microsoft account more convenient, and, as we’ve seen, perhaps even a little more secure (by not having to type in your actual account password). If you can log in with a PIN, you’re free to make your actual Microsoft account password long and complex — especially if it’s filled in elsewhere by your password vault — strengthening the security of things like your Outlook.com email, OneDrive online storage and more.

The downside, of course, is that signing in with a local account doesn’t get you any of the benefits of signing in with a Microsoft account, like synchronized settings across machines, integration with the Microsoft Store, and several Microsoft apps and applications. Nonetheless, it’s a choice some people make for a variety of reasons.

And, yes, you can sign in to a local account using a PIN as well, though the benefit is primarily convenience.

Do this

Subscribe to Confident Computing! Less frustration and more confidence, solutions, answers, and tips in your inbox every week.

I'll see you there!

4 digit pins are quite easy to sniff out as there really are not very many combinations of 4 numbers, however passwords are better because there are 26 letters in the alphabet plus a choice of capitals and symbols too. It would take a hacker much longer to sniff these out.

Did you read the article? Hacker’s don’t have the same level of access for a PIN as they do for a traditional password. And the article directly addresses the steps you can take to make a PIN more secure.

My biggest problem with the W10 pin is that there is no locking upon multiple failed attempts and it opens immediately when the correct pin is entered. For example, if you have the very uncommon and highly secure pin “1234”, someone can sit at the computer and keep trying. So if they tried the even more secure and slightly less common “123456”, they would get in after the 4th digit was entered. So, Leo, you are correct that to make it more secure, add more digits and don’t use something easy to guess.

Believe it or not, 123456 is more common than 1234 (as of Jan 2015 anyway) …

http://gizmodo.com/the-25-most-popular-passwords-of-2014-were-all-doomed-1680596951

…although, I have to admit, I find it hard to believe that ‘mustang’ beat out all of the available curse words and body parts.

But it’s not safer than 123456 because of poor design on the part of Microsoft, once you’ve entered the first four digits, 1234 Windows will log you in immediately before you have a chance to add the last two digits. I can’t believe the designers at Microsoft could be so stupid. Type in a bunch of numbers and count them as you type Windows will tell you how many characters are in the PIN.

“My biggest problem with the W10 pin is that there is no locking upon multiple failed attempts and it opens immediately when the correct pin is entered.” – This can be configured using Group Policy in the Pro, Enterprise and Educations editions, but not in the Home edition. I don’t see the omission as being particularly problematic.

As an aside on a separate technical matter, and taking absolutely nothing away from the arguments, but purely to correct the use of a specific word, adding an extra digit to a PIN does not make it “exponentially” safer. It makes it 10 times safer, and adding a second extra digit makes that now safer 5-digit PIN 10 times safer yet. An exponentially safer PIN would get safer at an even faster rate.

Actually adding 1 digit makes it 10 times safer. 2 digits makes it 100 times (10^2) safer. 3 digits makes it 1000 (10^3) times safer. Maybe I should have said “geometrically” (I don’t think so) but it’s important that it not be thought of as linear. 🙂

I’ve been computing for a decade, but this left me puzzled. I’m not alone in this I see. How does a PIN, (regardless of length), secure my local computer if I don’t enter it with keystrokes?

Please re-visit this Leo and speak to those of us who need it on a bit more pedestrian level. Sorry about the density but If I don’t get it I usually have company.

Thanks

Yeah, this seems somewhat nonsensical to me. If a keylogger is present on your system, it can log both the PIN and any passwords that you subsequently enter, including your Microsoft password (if you enter it). Leo’s contention would seem to be that you probably will not enter your Microsoft Account password after logging in with your PIN, so it will not be captured. While that may be true, any other passwords – banking, email, etc. – that you enter will be captured, and those passwords are likely more important than the one protecting your Microsoft Account.

All in all, I think keyloggers are pretty irrelevant to this discussion.

I don’t understand your question. You do enter it with keystrokes.

“The single biggest difference between using a PIN and a Microsoft account password to sign in to your machine is that the PIN only works on the specific machine for which you set it up.” – I’m somewhat puzzled. How’s a PIN tied to a device on a non-TPM enabled system?

You don’t need a TPM (chip) to generate or store a hardware signature. This has been done since Windows XP by storing the hardware signature (key) on the hard drive.

Indeed – which is basically how Windows Activation works. Anyway, I actually discovered the answer to my question:

“When the user has completed this process, Microsoft Passport generates a new public–private key pair on the device. The TPM generates and stores this private key; if the device doesn’t have a TPM, the private key is encrypted and stored in software.”

https://technet.microsoft.com/itpro/windows/keep-secure/microsoft-passport-guide

And that, of course, means the the process is less secure than on TPM-enabled systems.

… On the other hand, any new Windows 10 machine would be a TPM machine.

TPM may be required, but even so … I must be missing the point of your question. It’s local data, nothing more.

Hi Leo, I just wanted to add a comment about using your pin for sign in. You said you would lose synchronization across machines, but that didn’t happen with mine. I use a laptop and pin at work, and a desktop and password at home. I changed the desktop wallpaper on my home computer and the next day when I went to work, it was on the laptop when I fired it up. Kind of confused and surprised me since I really didn’t want it there.

Leo, you did a valiantly great job explaining why MS decided to use a pin. But, I’ll present a perhaps cynical alternative rationale. This is the type of goof that happens all too often in software, or for that matter in technical designs: Someone comes up with what they think is a great idea, usually trying to “fix” what ain’t broken. Then they discover that there is a hole (i.e. problem) with the design, so instead of undoing the problem, they tack on a patch to problem and somehow rationalize it. MS wanted to tie in the MS account to all computer log-ins for their marketing, so in Windows 10 they said you must use your MS account rather than a machine password. Then they discovered that this scheme wasn’t so secure – specifically, not secure for MS. So they invented the pin concept to protect MS accounts from being hacked, but not lose the association between a computer and the MS account. If machine login security was a real concern, then they could have just as easily tied in your machine password to the hardware signature.

What’s curious is that the pin doesn’t have to be all numbers. It can be configured to use letters and special characters. In other words, the same concept as the good old machine password, but now it’s tied to your hardware signature and indirectly to you MS account.

Of course, as Leo already said, if someone has physical access to your machine, none of this matters anyway.

I originally set up the machines in my house with MS account logins and a Home Group. We found that the logins were a nuisance because we use long passwords that aren’t easy to type. So we switched to PINs and the Home Group quit working.

Has anybody else had this problem?

Now you can use letters and special characters in your PIN. By definition, it’s no longer a PIN, Personal Identification Number, it’s a PIP Personal Identification Password or Passphrase. 😉

You can count on Microsoft for ridiculous naming conventions.