Mostly because there’s nothing to steal.

There’s still a fair amount of discomfort around the concept of passkeys as replacements for passwords. The most common objection is something like “So if someone has access to my machine, don’t they have access to all my accounts?”

The answer, of course, is more complicated than a simple yes or no. The important thing to realize, though, is that passkeys actually add a layer of security.

Passkeys & safety

Passkeys are a secure authentication method stored on specific devices that require user verification through mechanisms like Windows Hello. They enhance security by enabling passwordless sign-in and keep you safer by eliminating common vulnerabilities associated with traditional passwords and other authentication mechanisms.

Passkeys

In short, passkeys are digital keys assigned to a specific device by a one-time authorization process. This process may involve one or more other authentication mechanisms associated with your account. These may include:

- Password authentication

- One-time codes sent to email

- One-time codes sent to a phone

- One-time codes from an authenticator smartphone app

- Authorization on an already-signed-in device

- A one-time backup access code created when the passkey or two-factor authentication is enabled

Once set up, passkeys are stored securely on each machine and require you to authenticate each time they are used, typically via Windows Hello PIN, fingerprint, or facial recognition, or possibly with your Windows sign-in password.

By default, passkeys are valid only for the machine on which they’re set up. The only exception is that some password managers now also act as secure passkey repositories, allowing a passkey to be stored and used wherever that password manager is used. Once again, additional confirmation is required each time a passkey is used, either in the form of Windows Hello or by entering your password manager’s master password.

Help keep it going by becoming a Patron.

Hello?

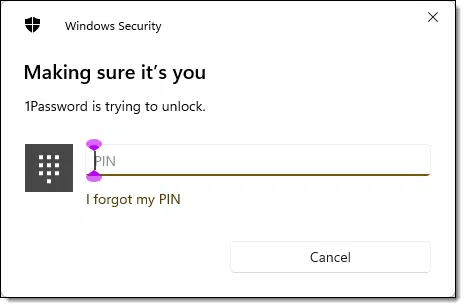

Windows Hello is another poorly named feature of Windows. It’s a technique of using either a PIN or biometrics to sign in to Windows. It’s something you enable on each machine. PINs, if used, are unique to each machine, and, of course, your biometrics are unique to you.

Because PINs and biometrics are quick, easy, and secure, Windows Hello is often used as a layer of additional authentication when you’re about to do something that requires extra security.

Like using a passkey.

Signing in

Let’s compare the different ways we might sign in to an online account.

Sign in using a password only

When only passwords are used, you manually enter your username and correct password to gain access.

Sign in using a password from a password vault

Using a password vault, you unlock your vault either with its master password or Windows Hello. The vault fills in your sign-in credentials for you or makes them easily available to copy/paste. Password vaults are more secure than manually entering passwords because they enable long, complex passwords without ever re-using a password.

Sign in using a passkey only

The first time you sign in to an account using a passkey, you’ll be asked to authenticate yourself using one of the secondary methods listed above. Once authenticated, the passkey is created and saved to Windows’ secure storage. This is repeated for each machine you use.

The next time you sign in on that specific machine, you’ll be presented with Windows Hello PIN or biometric authentication. That’s the passkey being used to sign you in.

Sign in using a passkey from a password vault

Using passkeys saved in a password vault, the first time you sign in to an account using passkeys on any machine, you’ll be asked to authenticate yourself using one of the secondary methods listed above. Once authenticated, the passkey is created and saved to your password vault.

The next time you sign in on any machine on which you use that password vault, you’ll be presented with Windows Hello PIN, biometric authentication, or your password vault’s master password prompt. Once confirmed, you’re signed in. The passkey will have been used to sign you in.

Practical applications of passkeys

Let’s examine the reality of using passkeys in two scenarios. The first one people ask about frequently: someone walks up to your machine, and because your passkeys are activated, do they have access to your accounts? The second — when your computer is infected with malware — is one people don’t ask about as much but I think is more important.

Scenario #1: Someone walks up to your computer

First: Is this a likely scenario?

First, let’s consider how likely or unlikely this scenario is for you. How often do people you don’t trust have access to your computer? If it’s never or rare, then this isn’t an issue. This scenario doesn’t apply to you, and you don’t need to worry about it.

Second: if the machine is signed out, locked, or turned off, the attacker needs your sign-in credentials. That could mean your password or your Windows Hello PIN. Without those, none of these scenarios apply. You’re done. They don’t have access to anything on the machine.

Now, if someone a) has physical access to your machine, and b) you leave your machine unlocked, as many of us do, then this scenario may come into play.

Here’s what’s required to sign in to one of your online accounts by someone who just walks up to your unlocked machine.

If you use passwords only

They need to know your username and password for each account. If they have that, naturally they can sign to any account and use it as you.

If you use a password from a password vault

If the vault is locked, then:

- They need to know your password vault’s username and master password…

- Or they need to be able to authenticate via Windows Hello if your vault is configured to use it.

- They may also need your two-factor key or code if your vault is configured to require it.

Without any of that, they can’t get in.

But what if you leave your vault unlocked? This is one of the reasons I recommend an auto-lock timeout in your password vault. If people can walk up to your machine, make it short. If it’s not really an issue but you still want to protect yourself, choose something longer. Since I have Windows Hello enabled in 1Password, I have it configured to lock after four hours (Windows Hello quickly unlocks) and require my full master password once every 30 days (and after rebooting).

If they get in, not only can they sign into whatever account they like, but of course they can run off with the contents of your vault, allowing them access to your accounts from elsewhere later.

If you use passkeys only

They need to know your Windows Hello PIN or your Windows password. (Theoretically, having your face or fingerprint would also work if you’re using biometrics.)

If they have those credentials, they could sign in to your passkey-protected accounts, but only from that machine. There is nothing to steal and nothing they can take to their own machines.

If you use passkeys from a password vault

If the vault is locked, then:

- They need to know your password vault’s username and master password,

- Or they need to be able to authenticate via Windows Hello if your vault is configured to use it.

- They may also need to use or have your two-factor key or code if you have your vault configured to require it.

In addition, when attempting to use a passkey stored in the vault, they will again be required to authenticate themselves with either Windows Hello PIN or your vault’s master password.

If they compromised your vault, then they can, of course, export everything — except the passkeys. Passkeys cannot be stolen. In addition, if your account is passwordless — requiring either a passkey or one of your backup authentication methods to sign in — they have no password to steal and thus cannot access the account.1

Scenario 2: Malware on your machine

What I consider to be a more likely and important scenario that people don’t ask about as much is when there is malware on your machine. How do passkeys relate to malware?

Malware can do anything, so we have to control what it can find. This is where passkeys really shine.

If you use passwords only

Malware containing a keylogger can slurp up your sign-in credentials.

If you use passwords from a password vault

Malware containing a keylogger can slurp up your sign-in credentials to any online account you sign in to and possibly to the password vault.

If you use passkeys only

There is nothing for malware to capture. Passkeys cannot be intercepted.2 The malware cannot sign in to your online account.

If you use passkeys from a password vault

If the password vault also uses passkeys for authorization, then there is nothing for malware to capture. The malware cannot sign in to your online account or your vault.

Passkeys significantly increase your protection from malware.

Going Passwordless

One of the interesting side-effects of passkeys, and, I suspect, one of their goals, is that they are more secure than passwords. In fact, if your account has a password at all, it’s ever-so-slightly less secure than a passwordless account using passkeys or any other authorization mechanisms.

Why? Because when alternative mechanisms are used exclusively, there’s no password to steal. There’s nothing to be caught by a keylogger, nothing to be guessed, and nothing to be exposed in a breach.

For example, medium.com accounts have no password. To sign in, you provide an email address, and they send a code or link to that email address. Your ability to receive that email and act on it gives you access to the site. There’s no password involved.

Passkeys make going passwordless much more convenient. Once set up, instead of waiting for an email, you simply respond to Windows Hello asking you for a PIN or biometric, and you’re done.

[Im]Perfect Security

“Yeah, but Leo, what about this scenario….???”

Whenever I discuss security — particularly account authentication techniques — I always get pushback from folks with scenarios that a) they don’t believe I addressed, and b) they believe make the entire argument moot because the perception of what they’ve “discovered” is so severe.

Sometimes I learn something. I love when that happens.

More often than not, though, it just points out that I didn’t explain a core concept properly, because that severe scenario is not only covered but covered well by the technology.

The other scenario is when they’re absolutely, positively, right, but what they’re right about is such an implausible scenario that it’s not worth getting worked up about.

There is no such thing as perfect security. You cannot be secure. You can only be more secure or less secure.

Passkeys help you become significantly more secure.

Do this

While unrelated to the above, my #1 tip for account security is to use two-factor authentication.

Then start getting familiar with passkeys. Enable it on one of your accounts (Google’s a good choice) and get a feel for how it works. I suspect you’ll find it quite convenient. I know you’ll be seeing it more and more.

Then consider making one of your accounts passwordless. Microsoft rolled this out some time ago. You’ll find the option in the security settings for your Microsoft account.

And finally, consider having your password vault store passkeys for you so you can take them from machine to machine. The reward for all of it is more freedom and fewer passwords.

Perhaps somewhere in there, subscribe to Confident Computing! Less frustration and more confidence, solutions, answers, and tips in your inbox every week.

Podcast audio

Footnotes & References

1: Unless, of course, they have simultaneously compromised one of your backup authentication methods.

2: Yes, yes, as I always say, anything is possible. Malware compromise of passkeys falls into the extremely extremely unlikely bucket… so unlikely as to be not worth considering.

I use passkeys and windows hello. I have a probably paranoid concern and perhaps this has been covered.

How good or secure are the algorithms at differentiating faces or fingerprints?

The video/article was great. I have a question that the topic implies. If you use passkeys on your android phone (and Windows laptop) to log in to Google, will this stop Sim swapping? Intuitively, once a new phone signs in to Google (using I’d and password) that should be rejected pending approval from other devices with the passkeys. Would this be adequate to stop this scam?

I believe you are correct. The passkey should be unique to the device, not the SIM.

Hello Leo

Love your stuff…

I am weary about this whole new concept, maybe i am just getting on in years like you.

Scenario… Considering you look like you weigh roughly 150 (US), lets say for arguments sake grab you, your fingers and your phone one evening as you step out of the 711, bag you, and load you in my van and drive you somewhere private, how much of your life have i not made my own by Sun up?

See i am in South Africa, what i am sharing with you here is not an arbitrary fantasy, it happens here many times every day, especially to vulnerable Females and little old Men. In my World the operative question is not “how little can they take”, it is “how easily can you be taken”, and take you they do, even if it is then just to play with you for the evening if nothing else can be pealed of you… Some are however sophisticated enough to watch you and learn how they will commit their next crime.

Would love to see a vid on this kind of thinking from you sometime.

Wolf

I am trying to be receptive to the passkey concept. However, I struggle with this process all depending on the security of the Windows Hello PIN (only 4 numbers) – I can’t do biometric on my pc.

So, the way I see it, I am now depending on a 4 digit “password” to protect me. Hmm, I thought we needed 15+ characters (a mix of upper/lower case letters, numbers and special characters) to create a (somewhat) secure password??? I also understand this passkey is machine specific and the threat of a hacked Hello PIN is only for that particular machine… but it is still a major breach of security for THAT machine and all sites that use passkeys on THAT machine and they all only need the Hello PIN for ‘verification’.

What am I missing?

1) that PIN is for that machine only (different machines can have different PINs), so the attack surface is dramatically reduced.

2) Windows will let you make PINs that are alphanumeric and of arbitrary length. Like a password.

3) They would need access to BOTH your machine and PIN. That’s a combo that rarely happens for average folks. (If you’re a high value target, your comment is spot on, but mitigated by using a password-like PIN).

My Windows Hello PIN is much longer than 4 characters. This would be as hard to crack as a password of the same length, actually harder as they would need to do it on my machine.

I wish it worked. The list of supported sites only includes three I have ever visited.

PayPal.com So I tried. In 1Password, click Use passkey for PayPal. I login the old way. Click on Passkeys Manage. It says “A passkey can’t be created on this device or browser. To see what’s supported, visit our FAQ.” Click on FAQ. It says “This article doesn’t exist or has been unpublished”. One down, two to go.

Target.com. Works, but I have only used target.com twice it several years.

Ebay.com. 1Password does not suggest passkeys? ebay.com does not mention passkeys at all?

Similar to my Yubikey. I only use that for the VA.gov via id.me.

cecil

Did you know that the good old legacy password is also “stored securely on each machine”? It happens to be in the registry, but encrypted. So, now we have a “new” way of doing things. We “securely store a passkey on each machine”?

In the good old password days you would type in your password to get into a machine. The “new” way is to type in a pin, which can look very much like a password, to get into the machine.

No matter how the details of access control change, there is one fundamental element that must remain the same: the machine has one key and you have another key, and these two keys must somehow match or sync. You can call it “passkey”, “pin”, “password” or “frank”, it all boils down to the same concept.

When someone invents a method that doesn’t follow this concept, then please let me know. Luckily Leo covered himself by ending the article sensibly with “There is no such thing as perfect security. You cannot be secure. You can only be more secure or less secure.” The jury is still out on passkeys. Remember that for that last 65 passwords protected everything.

SIM swap risk – still applies if the phone no associated with the SIM is used for TFA on an account (e.g. banks which are really behind the curve on security).

Leo, you’ve emphasized the association of a passkey with a single device as part of the security model.

If a Password Managers stores a passkey that is used across multiple devices does this not compromise the security model.

No more than storing passwords, as long as the password manager does security right and you protect your vault with a strong password and never write it down or leave it open where someone else can access it.

That’s actually addressed in the article. What am I missing?

Windows Hello PIN Codes

I wonder how many users use a different PIN code for each device?

Excellent comments and replies. I learnt something. Thanks Leo and staff.

Leo, this would be an ideal topic for a book with flowcharts etc. Anything like that in your pipeline?

Hi Leo very interesting article and I’m intending to using Passkeys on all my critical email accounts but I’m struggling to understand how my outlook desktop or IOS mail app can retrieve emails from multiple email accounts using passkeys or can’t I use mail apps once passkeys have been enabled on an email account?

I haven’t seen any examples of it in use for desktop email programs yet. My GUESS is that much like 2FA, you’ll end up using “app passwords”, OR the authentication will be handed off to the service in question (via OAUTH) which would use passkeys on the device. But as I said, just a guess.

I have the same question as Dave Hart about using passkeys in a vault on different machines. Leo, you reply with “I wonder what I am missing”, but I actually wonder what *I* (or he and I) am missing….

You mention in your final conclusion “consider having your password vault store passkeys for you so you can take them from machine to machine.” Does that imply that the vault stores different passkeys for the same account on different machines? If not, I really don’t get it.

No, the vault stores a single passkey, as I understand it. The passkey it stores works on all machines where you can open your password vault.

I was an early adopted of Passkeys, the same day that Google announced them.

In my opinion, a better invention than the invention of sliced bread!

No more fumbling with passwords & @SV/FA, and a faster and more secure (so far at least) wy to sign in.

“There is no such thing as perfect security. You cannot be secure. You can only be more secure or less secure.

Passkeys help you become significantly more secure.” Excellent comment, should be on the desk of each computer user!

Hi Leo great article I am about to use passkeys wherever I can but just before I do I have one worry. I have multiple email accounts (4 Microsoft and 4 Gmail ) which I access using Outlook desktop. If I enable passkeys on all email accounts can Outlook desktop still retrieve them?

It should. Make the transition one account at a time.

I have 2 banks and 3 credit cards. None use passkeys or yubikey. I am 79. Please ask them to hurry.

I’d look for a bank that uses passkeys or an app. My banks use apps to authenticate logins. Pretty much thesme level of protection, but passkeys are easier.

What about someone who has a “legitimate” reason to ask you for your Windows sign in credentials. For instance, someone repairing your laptop. It is then purely a matter of trust that they don’t access your online accounts.

That’s the case today. Passkeys don’t really affect that, I don’t think.

Every time I log in with a passkey, it asks for a confirmation using a PIN or biometrics. That’s one reason a confirmation is required.

I recently began consulting your YouTube videos & have found them quite informative. This encouraged me to search your website for advice on particular topics. After reading a couple articles I noticed that they lack the date that the article was posted. I would value this information because the rapid pace of technology places a premium on current recommendations. Would you please consider adding the date that you post your articles? So far, my only indication of an article’s date comes from the comments posted by other AskLeo subscribers.

Every article is dated, at the bottom right.