Only if it’s the only option.

I’ve noticed recently that a number of websites allow you to log in using another web service instead of directly from that webpage. For example, my son couldn’t remember his password at PhoneZoo, but it had an option to log in from his Facebook page. He pressed the button, logged into Facebook, and he was also logged into PhoneZoo.

Can you explain a little bit about what’s going on here and whether this means there is an increased security risk? If someone gets in his Facebook account, I would assume they could also get into his PhoneZoo account or any other website providing this access. Is this a trend, and is there any way to avoid it?

Rarely do I get to be this absolute: if it’s presented as an option, don’t use it. Log in with a traditional email or ID and password instead.

There are a variety of reasons, but the most important is simply basic security.

Should I log in with Facebook?

- Using a unique login ID and password for each service is much more secure.

- If you must use it, make sure your Facebook account is secured.

- The service does not get your Facebook password.

- Facebook gets information about every service where you use Log in with Facebook.

- Using the same account everywhere is even less secure than using the same password everywhere.

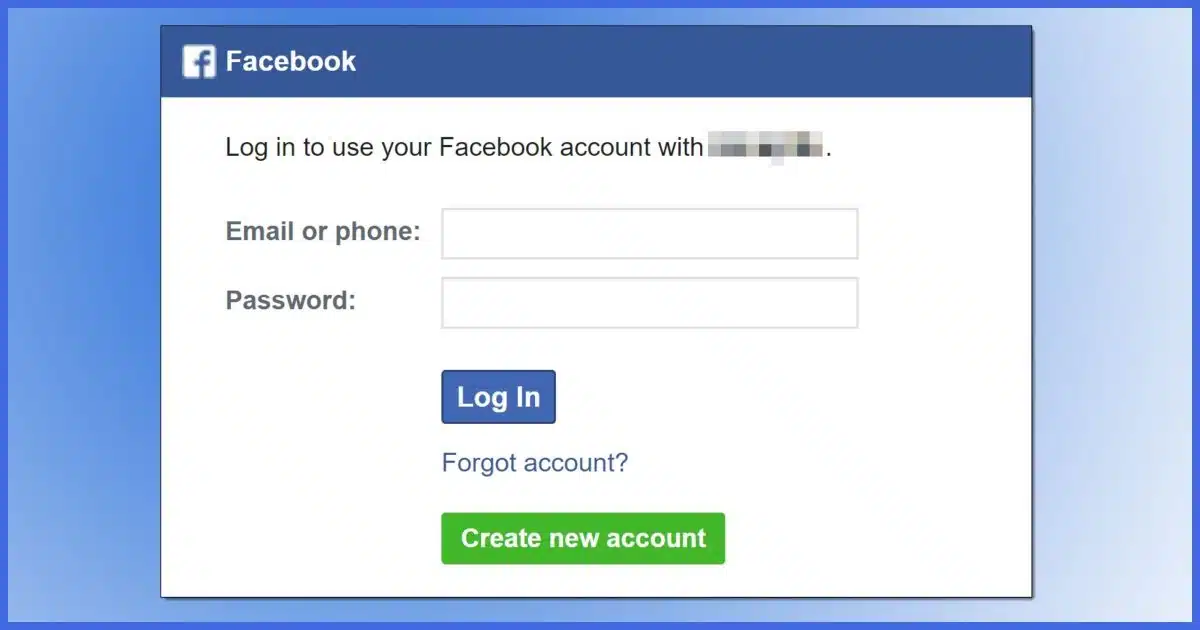

Log in with Facebook

Using services like Facebook to provide authentication is a popular trend. It’s not just Facebook: you can use your account with Google, Twitter, or other accounts to log in to many unrelated services. (Throughout this article, I’ll use Facebook as my example, but the same issues apply to using other services. I’ll also refer to all the services that you’re logging in to, like PhoneZoo in the original question, as third-party services.)

In most cases, it’s an option. You can log in traditionally by creating your own account, usually with email and password, or you can choose from one of the other authentication providers, like Facebook.

In some cases, it’s not an option. The third-party service has elected not to provide its own sign in and relies entirely on using other platforms to authenticate its users.

These third-party services want to make it as easy as possible for you to sign up with them. Not making you create yet another account and password to manage is one way to do so. It also means they don’t have to maintain their own authentication infrastructure.

Help keep it going by becoming a Patron.

They don’t get your Facebook password

A common concern is whether these third-party services get your Facebook login ID and password.

The short answer is:

- They usually get your ID (your email address, in the case of Facebook), which generally becomes your user ID on the third-party service.

- They do not get your Facebook password.

This practice uses an industry-standard protocol called OAuth, short for Open Authorization. You authenticate directly with Facebook, who then tells the third-party service that yes, you are who say you are by virtue of having successfully logged in to your Facebook account.

They may get additional information

When you set up your account with the third-party service and use Facebook to log in that first time, the service may request additional permissions. They may ask for additional information from your Facebook profile, such as contacts, permission to post to Facebook on your behalf, or more.

When this happens, you’ll be notified exactly what additional permissions and information you’re allowing to be shared, and you’ll be given the opportunity to either alter the permissions or abort the login completely. Be sure to read these carefully so as not to give more access than you’re comfortable with. Unfortunately, you typically can’t pick and choose which permissions to give — in my opinion, yet another reason to avoid Facebook-based logins.

Facebook gets information

When you use Facebook to log in to these third-party services, you’re telling Facebook which third-party services you use.

Given the concerns people already have about how much information Facebook collects, explicitly giving them even more seems a little counter-intuitive.

Facebook settings record which services you’ve used Facebook to sign in to. It might be a longer list than you remember.1

The same password everywhere is bad enough

Security experts and tech writers such as myself frequently advise against using the same password everywhere. If one account gets hacked and your password is exposed, then all your other accounts that use the same password are at much greater risk of getting hacked as well.

By using Facebook for authentication, you’re using the same account to sign in everywhere.

If your Facebook account is ever compromised, then every other account where you use Facebook for login is immediately compromised. Someone with access to your Facebook account can quickly and easily determine exactly which other accounts you have and access them.

Separate accounts are more secure

I heartily recommend setting up a unique login ID and password for each online service that requires you to sign in.

This limits the exposure of any one of them getting hacked to only that single service. It also removes the possibility of accidentally allowing them access to your Facebook account information for other purposes.

Yes, that means unique passwords for every site. The best way to manage that is to use a password manager, which allows you not only to manage all passwords without needing to remember them but enables you to use long, complex, safe passwords for each account.

Do this

If you’re not convinced and the appeal of using your Facebook login everywhere possible is just too compelling, then secure your Facebook account as best you can. At a minimum, that means using a long and strong password and adding two-factor authentication.

But I strongly recommend you use unique login IDs and passwords wherever possible instead.

I also recommend that you subscribe to Confident Computing! Less frustration and more confidence, solutions, answers, and tips in your inbox every week.

Podcast audio

Footnotes & References

1: It was for me.

“There’s no way for PhoneZoo (or any of these services) to associate an existing account that they have setup with a Facebook account that you then use to login later.”

Many sites will let you tie your Facebook login and your unique site login together if you create separate accounts for each.

If you choose to login to a site via Facebook, does that create any kind of tie between your Facebook account and that site? I’m envisioning something like this:

– I log into skeevysite.com with my Facebook account

– A Facebook friend of mine also logs into skeevysite

– My Facebook friend sees my Facebook account profile listed on skeevysite’s page, under “Friends Of Yours Are Also Members of Skeevysite!”

– Or, skeevysite posts to its Facebook account, “Veronica has just joined Skeevysite.”

– Or, skeevysite posts to my Facebook page, “Veronica, we’re so glad you’ve joined Skeevysite!”

(Not that I actually do anything scandalous on the internet…I’m just a privacy-minded person.)

I think it’s a major breech of security to even ask for your Facebook log-in information on a 3rd party website. Asking for your hotmail, yahoo etc. information is the same deal.

Like the author stated, although a pain, create a separate username/password for each and every website you wish to be a member of.

The security risk is likely greater than you can possibly imagine if you start freely giving away info. to 3rd party sites. Don’t do it.

There’s another danger. There’s a chance that they could offer you to log on through Facebook and send you to a Phishing website which looks like Facebook and steal your Facebook login.

I don’t use the system mentioned to log on to any other site through F.B. but I do know that many times I’ve searched online parts sites for electronics & what not and it’ll come up with a message or page that states ” Like this such & such site? click like to link this site with your F.B. account and let your friends know you like our site” etc… which in turn links your F.B. to the site your shopping/searching/etc… & posts a message on your wall, now time line or whatever, that you “like” such & such site and linked it to your F.B. account and asks your friends if they want to visit said site click “like” blah, blah, blah.

Quite the involved nuisance if you ask me.

I keep everything separate & use LastPass to keep track of the ID’s & Passwords if I want to join the site/forum/store I’m interested in.

Using the login credentials from a service like Facebook as a form of authentication for another service is really no different than the SSO (single-sign-on) authentication that a business may use. SSO authentication makes it possible for an IT department to centralize user accounts and login credentials in a secure way and then employees/users do not have to remember as many sets of usernames and passwords. The primary differences between the two situations is that using a service like Facebook is free and a highly-targeted online resource and that a lot of data (from the free authentication service and the other – also most likely free – service) is being mined for (most likely) advertising purposes).

Hi, I just have a concern about storing all my important passwords in lastpass!, how can you trust them ultimately with all of your important passwords?? And what happens when lastpass gets hacked and everyone’s important passwords get breached!!!!?.

Cheers

The password vault is stored encrypted on the LastPass website. LastPass can’t see your password. If you use a long, strong, unguessable (no dictionary words, at least 14-20 characters long), your file should be uncrackable. LastPass, themselves, cannot open that file.

I trust them because (and this is important) they can’t see my passwords. The only thing ever uploaded is encrypted data that they don’t have the keys to decrypt. Only YOU do by virtue of knowing your master passphrase.

They’ve never been breached (all rumors to the contrary are actually wrong — they took proactive action once when they saw suspicious network activity, but never once has LastPass data been compromised). And once again, even in the event that they had been breached, all the hackers would have is encrypted data with no way to decrypt it.

Agree with Leo and Mark. In addition you can use various forms of 2 factor authentication and also restrict logins to only be from specified countries (which you can change at anytime if you are planning to travel).

I have used LastPass on phone, tablet and laptop, for a number of years and now cannot even remember any of my passwords. That’s how confident I am that it is safe and secure.

You could also use KeePass – it is open-source and you can store your passwords wherever you want. And while I will always take any opportunity to plug KeePass, I would not be afraid to use LastPass.

I use pass (https://www.passwordstore.org/) and store them all on my laptop. I just back my laptop up to a few external hard drives.

Pass may be a great program, but I prefer a more widely used program such as LastPass or LogMeIn because widely used programs have been tested much more in millions of computers. That gives me more confidence that most of the bugs have been ironed out.

What is your view of Dashlane?

Is it as secure as LastPass or LogMeIn ?

How can you truly know that in any of these password managers “they can’t see my passwords”?

And how can you know that they’ve never been breached?

Would they really publicize a breach?

And if you are even talking about breaches, that gets me to worrying.

You may have confidence that “most of the bugs have been ironed out,” but how about the bugs that as yet haven’t.

Ultimately I am assuming that there is a human being who can interpose him/herself in the chain of encryption somewhere, assuming the encryption has been set up properly to begin with.

I have always been taught: “Never say never.”

LastPass, specifically, was analyzed some years ago by Steve Gibson — a geek that many of us in the industry trust for his ability to analyze software and how it works. The rest is all about trust.

Look, if you don’t trust them, then don’t use them. Nothing says you have to use them. You’re just giving up the convenience that many of us who do trust are afforded. I happen to trust LastPass because of Steve’s analysis, and because of everything that they have said publicly.

Whatever technique you use, make sure you use LONG STRONG passwords, and DIFFERENT passwords for every site. And however you keep track of them yourself, make sure THAT is secure as well. (No post-it notes, for example. 🙂 ).

Or, you could use KeePass (can you tell I recommend them?). It is open-source, so you can examine the code and see for sure that they are not “seeing your passwords”. I do love and use KeePass, but it’s not because I don’t trust LastPass – I would be confident to use them, I’ve just never felt the need. I guess it’s a matter of where you want to take the risk – I think it’s far *less* risky to use a password manager than *not* to use one. (Not to mention convenient.) Good luck!

A bit off topic, but equally as important – all readers should visit Steve Gibson’s site and run the security tests offered.

If hackers get pasword 4 one account how do they automatically know what other accounts you have?

They don’t automatically know. They just try the email (or username)/password combination on a number of websites and see which ones work.

What is wrong with letting win 10 remember your passwords?

Windows 10 doesn’t offer to store your internet passwords. Your browser does. Browsers don’t have as good encryption security as programs like LastPass of LogMeIn.

Is it safe to let my browser remember passwords?

Okay, I get it. Don’t use Facebook or Google to sign-in. But here’s the unanswered question, i.e. how do you recover from this error? If you’ve already did this “unthinkable idiot” move at a website as I unfortunately have, how do you undo it? Do you just establish another login and don’t use FB/Google link again? Or is it just too late ‘cuz FB/Google already has your info and just continue using FB/Google sign-in method?

That’s a very good question. Yes, Google/Facebook has your information to date.

I would (and in some cases have):