You don’t have to use a password to be safe

I was reading about passwordless logins and how great they are. Better and more convenient than long complicated passwords that we might use with a password manager like LastPass. I enter my username and click Continue and then press another button to have a link emailed to me. I then go to my email and click the link in my email and voila! I am automatically logged in.

Well that certainly is easier than remembering a password, but I don’t get how it’s more convenient given the number of clicks to get logged in compared to allowing LastPass to fill in the user name and password so that I only have to click one button.

But what I really don’t understand is how this is a more secure way of logging in. Are passwordless sign ins safe? Should I be worried about companies wanting to move to passwordless?

Worried? Nope. Not at all.

It can be a convenience, for sure. As to whether or not it’s more secure, my take is is yes — but we need to understand the scenario it protects you from to be confident about that.

Signing in with only an email address is almost a backhanded approach to two-factor authentication. By proving you have access to that email account — by clicking a link emailed to you — you’ve authenticated securely and need nothing else. The site using this technique is relying on your maintaining the security of your email account appropriately.

An example: medium.com

Let’s start with an example.

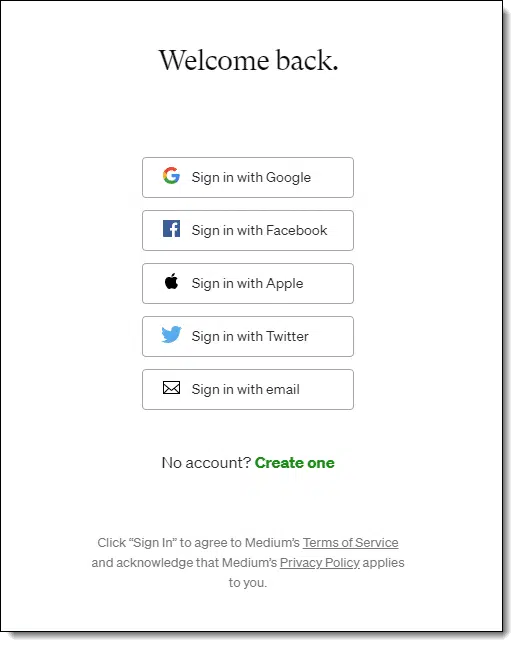

Medium.com is a popular site that offers several different approaches to signing in.

You can, of course, use the other services listed — Google, Facebook, Apple, and Twitter — to sign in using your credentials with them. I prefer to keep all my accounts separate, so I set my Medium account to “Sign in with email”.

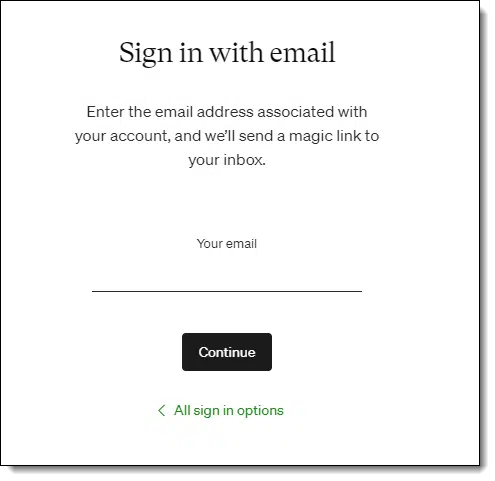

When I first set this up, I expected to be greeted with the opportunity to set a password. Nope. When I sign in, it asks for my email address and nothing more.

My account has no password.

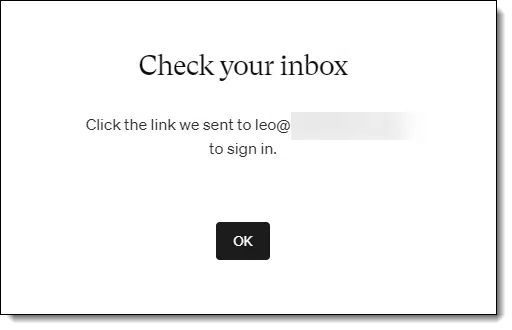

Instead, when I enter my email address and click Continue, Medium tells me to check for a message in my email account.

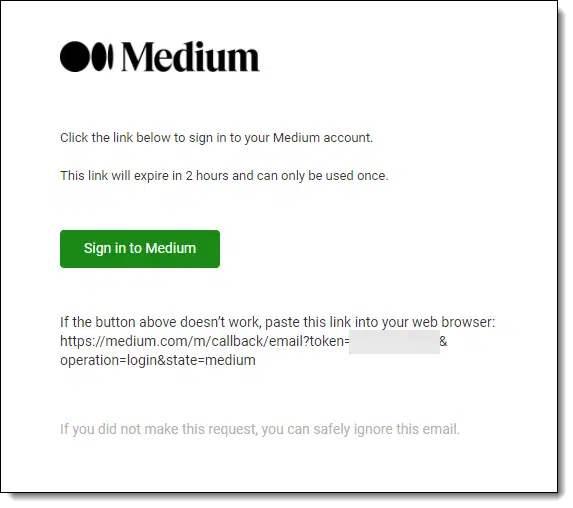

Sure enough, an email arrives.

Click the link, and I’m in. It’s that simple.

Help keep it going by becoming a Patron.

Passwordless sign in: convenient … maybe

It is simple, but is it more convenient?

Maybe.

The biggest issue I have with it is that it assumes email is relatively fast — but email is not guaranteed to be fast at all.

In my case, because of the way my email is routed, it can actually take two to three minutes before the email message with the sign-in link appears. I have to wait.

A more traditional email-and-password approach allows me to sign in without the wait at all. If the site is important,1 I’d prefer to be allowed to add two-factor authentication of some sort.

It also makes the assumption that the device you get your email on is the same device on which you want to sign in to Medium. If they’re different, it can be quite cumbersome to sign in — to the point of just avoiding doing so.

But it is more secure.

Passwordless sign-in: safe, almost certainly

This feels a lot like two-factor authentication. It’s not, but it is similar.

Maybe I’ll call it a factor-and-a-half authentication.

“Something you know” is reduced to only your email address. I’ll think of that as half a factor since it’s so easy for anyone to discover your email address.

“Something you have”, however, is your ability to click a link sent to your email account. That proves you are who you say you are, as identified by that email address.

In order to sign in, you must prove you have access to the associated email account. That’s all.

And as long as you keep that account secure, it’s enough. The only way someone could hack into your passwordless authentication is if they first hack your email account.

Perhaps most importantly, there’s no password to fall into the hands of hackers. Even if there were some kind of data breach at a company using passwordless authentication, there’s nothing there to steal.

It’s pretty cool, actually.

Security’s still on you

Now, to be clear, this doesn’t absolve you of responsibility for your security. In a sense, it just moves the target to something else you’re hopefully already keeping secure: your email account.

Therefore, my medium.com account is as secure as my email account. My email account (via Gmail) has a strong password, two-factor authentication, and so on — you know, the usual litany of advice we hand out about keeping your account secure.

But I do still wish I had the option of a quicker sign-in with a more traditional password approach.

Other forms of passwordless sign-in

The examples above all talk about using email as your authentication mechanism: prove you can access email sent to that account, and you must be who you claim to be.

The same can be done with other authentication methods. The most common might be fingerprint scanners and facial recognition. In addition to being used with a password for two-factor authentication, it’s not uncommon for them to be the only factor used to confirm you are who you claim. It’s also quite convenient, and probably faster than waiting for email.

Similarly, sign-in with PIN is another form of passwordless sign-in, though I consider it to be closer to single factor rather than the factor-and-a-half I made up above. A PIN is nothing more than another “something you know”.

I tend to agree with the material you were reading: passwordless sign-in has interesting potential to make our lives easier by needing to remember fewer passwords.

But I’d still prefer it to be optional.

Do this

Subscribe to Confident Computing! Less frustration and more confidence, solutions, answers, and tips in your inbox every week.

I'll see you there!

Podcast audio

Footnotes & References

1: Not that Medium isn’t important, of course. It’s just that, say, my bank is more important.

I agree that passwordless access is “better”, but it is still connected with a password – the password connected with your email account. So if your email has been successfully hacked, someone else now has the ability to set up all sorts of other accounts in your name and then quickly change the associated email for future invisible access. That invisibility is as simple as going back in and deleting the authentication email. Am I explaining that clearly?

Seems like a really good vector for phishing emails – send out enough “click here to access your medium account” emails, and you’re bound to hit someone who’s currently trying to log in (especially if this method of logon becomes ubiquitous) . . .

I’ve never used this type of verification before: in this situation, it sounds like you would *have* to click on the link in the email to gain access to your account – is this correct?

Seems to be, yes.

That’s a good question. It may be a vector for phishing but I believe it infinitely less susceptible to phishing than a normal login. If you click on the link they send in your email, you are automatically logged in to the website. If it takes you to a login page, you should be wary as a passwordless sign-in won’t ask you for a password. So if clicking on the link asks for a password, don’t enter it.

And if they happen to catch someone who is coincidently trying to log into a website they are spoofing, they’ll have both the phishing email and the legitimate login email in your inbox.

Good point – I didn’t think of that.

“So if clicking on the link asks for a password, don’t enter it.’

You couldn’t if you wanted to — the whole point is that there ain’t no password!

I’m laughing out loud here. Passwordless? Hardly! A password (or passphrase) is absolutely still needed… to access your E-Mail.

If your E-Mail is completely unprotected (not sure how that would work, but bear with me, it’s a thought experiment), then this technique would fall to the ground.

Another thought: This is seriously beneficial to the company using it.

Why?

No need for that massive databse of hashed, salted passphrases!

If the userbase is in the thousands, the hash database would be humungous — and with passwordless login, they could simply trash it* and recover all that valuable storage space!

—–

*By which I mean securely wiping or “fileshredding” it, not merely deleting it!

Not so humungous. If the hash were a kilobyte per user, much more than a normal password hash, a database of one billion users would be one terabyte. I have more storage on my PC. That’s pretty insignificant for a service with a billion users.