It requires your participation.

In a recent article, I discussed the different ways that various forms of two-factor authentication (2FA) can be compromised and which are the most resilient.

I need to explain one of those approaches in a little more detail, since it targets perhaps the most popular form of 2FA: the one-time password. If you’re not wary, you could fall victim.

The good news is that this attack requires your participation. The bad news is that you might not realize it until too late.

Hacking OTP 2FA

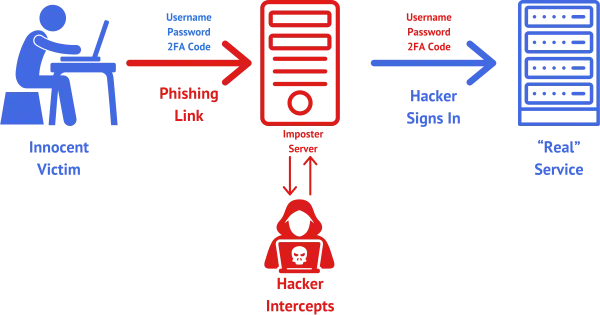

One-time-passcode (OTP) two-factor authentication (2FA) methods can be vulnerable to phishing and man-in-the-middle (MITM) attacks. Attackers try to deceive you into providing your 2FA codes and then use them in real time to log in as you. 2FA remains a critical security measure; hardware keys offer the strongest protection against these attacks.

It relies on phishing

From that previous article:

You click on a phishing link that takes you to a fake page looking exactly like one of the services you use. You sign in with your username and password, handing that information to the hacker.

This is the scenario 2FA protects you from. Even if you hand your password over to a hacker, they can’t sign in because they don’t have your second factor. One could even say this is the whole point of two-factor authentication: protecting your account even if your password is known.

Help keep it going by becoming a Patron.

It relies on man-in-the-middle

Continuing that prior article:

The hacker quickly signs in to the real service as you. They are presented with the real two-factor request, and a code is sent to your phone. They then present you with a fake two-factor request. You type in the code you got via SMS, thus giving it to the hacker, which they use to complete the sign-in on their end.

(Note that a code sent to your phone can include a code displayed by your one-time-passcode (OTP) device, such as Google Authenticator.)

It’s called a “Man in the Middle” (MITM) attack. It’s technically more complex for the hacker, so it’s not quite as common as the first scenario.

But it’s still dangerous when it happens.

MITM step-by-step

Let’s go through a MITM attack step by step. For this example, I’ll say it’s your bank.

- You receive email purporting to be from your bank and offering you a link to click to access your account. But it’s not your bank; it’s a phishing link from a hacker.

- The link takes you to an imposter website crafted to look exactly like your bank.

- The imposter site presents you with a sign-in. Because it looks like your bank, you don’t realize it’s not, and you enter your username and password.

- The hacker intercepts and collects your username and password.

- The hacker begins to sign in to your real bank website using your credentials.

- The bank responds with a request for your two-factor code — either SMS or a OTP provided by an app.

- The hacker passes this request back to you, again looking exactly like your bank.

- You enter your two-factor code.

- The hacker intercepts your two-factor code.

- The hacker enters the two-factor code into his attempt to sign in to your bank.

- The hacker now has access to the account.

Typically at this point, the hacker changes the password on your account or wreaks whatever other havoc he or she had intended.

And of course, while I used your bank in the example above, the scenario can happen for any account protected by code-based two-factor authentication that a hacker chooses to target.

Solution #1: Avoid phishing

I know, I know, this almost sounds like the old joke of telling your doctor “It hurts when I do this” and the doctor responding “Well, don’t do that.”

No one intentionally falls for phishing. But here’s the thing: the hackers are getting more sophisticated. Their attempts to fool you are getting more and more realistic. I’ve come close to clicking on that link a time or two myself.

Pay attention to your email program and spam filter. If they say something’s possibly dangerous, examine the destination carefully before you click. Yes, there are false positives (flagging something as untrustworthy when it’s really OK), but they’re not that common. Better to be more suspicious regardless.

In fact, here’s the real safeguard: don’t click the link at all. If the message is something you feel you need to investigate, then instead of clicking the link in the email that is supposedly from your bank, ignore it. Just go to your bank’s site directly — by typing in its address or using your own known good bookmark — and sign in. If there’s an issue, it should be shown there.

If you’re still not sure, give the bank (or whatever site) a call. Most1 would much rather answer your question than deal with the fallout of a compromised account.

Solution #2: a hardware key

Hardware keys are a second factor that plugs into a USB port.

When asked for your second factor, you insert the key into a USB port and push the button.

Hardware keys are impervious to phishing attacks. There’s nothing you can give the hacker that would allow him to fake having your key.

Naturally, a hardware key is a little more inconvenient for you, as you need to physically have it with you in all situations where it might be needed — but that ends up not being quite as bad as it might sound. Certainly for your most important accounts, this could be your safest 2FA alternative.

Do this

Honestly, one-time-code two-factor authentication is perfect for most people, even though in theory it’s vulnerable to man-in-the-middle attacks. These attacks are relatively rare, usually target specific individuals, and are easy to avoid before they even begin: just don’t click on that link.

Most important is to use some form of 2FA. Any 2FA is better than no 2FA.

Podcast audio

Footnotes & References

1: Sadly, not all.

And again, a password manager is a great extra layer of protection. It won’t fill in the login credentials because it doesn’t recognize that fishing site as legitimate. If your password manager doesn’t fill in the login information, the email is a scam. Of course, other errors may cause the password manager from logging you in, but those are so rare, it’s safest to assume it’s a scam.

If the password manager doesn’t fill in the password, don’t go into the password vault and copy and paste the password. unless you are absolutely 110% sure it the correct site.

Unfortunately, not every online service (including banks) is setup for using a hard key. Plus, one needs to purchase a hard key (preferably two or more for redundancy in case the key is ever lost or damaged). I bought my hard keys (Yubikey) from Amazon for about $60.00 $Cdn. each. (For Yubikey, see their web site, top-right menu item “Resellers” and then enter your location/country to pull up a list of vendors, or you can order directly from Yubikey). Google has its own hard key (I believe it’s called “Titanium”). Not sure what services other than Google it works with.

I use face recognition on my phone to verify.

How do you determine whether or not an online service supports a hard key.

You’d have to check their documentation. It’s usually mentioned as part of the process of setting up 2FA.

Hi Leo:

Thanks for this. The first time I was encouraged to use an alt method particularly hardware key I both didn’t want the trouble and realized it might be more dangerous as I would be taking my method “on the road” with me. I have always opted for opening any of my sites directly rather than clicking on links even when it seems legit.

This along with 2FA I’m hoping is more than adequate. I like avoiding any more complications or players in my e life.

Unfortunately some sites do not make it easy to login without using the link provided in the e-mail.

Fortunately 2 that I receive each month are both to view / download statements & are not transactional (mobile phone and an investment account), but no responsible organization should be inviting access via an embedded link.

Unfortunately, banks are notorious for lapses in security. My bank (not to mention any nams, but it’s the largest consumer bank in the US) sends me links to view my statements. I’ve written them about that with no response. They should have a line in the email telling you to go to their website and log in, and xplain that it is dangerous to click on email links. It’s not hard for people to do that it’s only 3 letters before the .com that everybody knows.

I don’t have much to say on this topic. I NEVER click links in email messages, EVER! And I always check the URL on any webpage where I have to click a link to either login, or authorize any action. I use a password manager to log in to any site I visit, and have an account with. If my password manager doesn’t fill in login information on any site for me, I carefully check the URL to ensure it’s the page I think I should be at. If it appears to be, I open my password vault, and use the site launcher for that site, rather than the page I was on. I may take a few extra steps, and surrender a bit of convenience in doing so, but I think I’m much safer for doing so.

Ernie (Oldster)

I STRONGLY agree with Mark Jacobs’ comment above. And it’s not just banks, it seems to all financial institutions, such as Fidelity and Vanguard and medical ones too, and I’m sure many more.

What I wonder is the use of VPN. I thought that a VPN connection is a protection against MITM. It is not mentioned here, or am I wrong?

A VPN encrypts the connection between your computer and the VPN server. It offers no protection against man in the middle attacks.

VPN does not protect against man in the middle. It protects you as far as the VPN servers, but after that the connection from the VPN servers to your final destination remains on the open internet.

Many thanks for this all-important discussion. In the case of a Yubikey, for example, you need to know its PIN in order to arrange 2FA with the likes of Microsoft (for a personal account). Unfortunately, getting the PIN from the horribly complicated Yubico website is “the Devil’s own work”. Despite my repeated protestations, the firm appears indifferent to simplifying matters.

Be warned! The more AskLeo! subscribers who also complain, the better!

Sadly, the sites where preventing access is the most important – you know, BANKS and BROKERAGE ACCOUNTS seem always to be the ones most reluctant to keep pace with the latest methods of security – I’m sure this is because the the antiquated infrastructure with which they must interact, but that doesn’t make it any less frustrating.

Leo, you wrote:

“…don’t click the link at all. If the message is something you feel you need to investigate, then instead of clicking the link in the email that is supposedly from your bank, ignore it. Just go to your bank’s site directly…”

And that, of course, is the whole thing in a nutshell. Don’t click web links in E-Mail. Period, end of sentence.

Just… Don’t.

Ummm, I got to this article by clicking a link in an AskLeo email…

If you’re sure the email is from the source it claims to be from, and you trust that source, then it’s fine to click on the links.