More cryptographic magic.

There are a number of ways to “do” two-factor authentication; for example, you may have used SMS text messages, codes sent to alternate email addresses, or codes sent to your phone.

Each of those has their pros and cons, and most are quite sufficient for average use. Of course they’re all more secure than no two-factor authentication at all.

One you might not hear about that often is the hardware key. The most common brand that you might have heard of is YubiKey.

Hardware keys are considered the most secure form of two-factor authentication.

How does a YubiKey work?

After associating a hardware security key with your online account, you’ll be asked to provide it later if two-factor authentication is required. These keys operate by provided securely encrypted one-time information that can be confirmed as authentic by the online service, proving you are who you say you are, or that you at least are in possession of the proper security key.

YubiKey

I’ll be referring to YubiKey throughout this article, as it’s the most common and most recognizable name, but other brands are available.

Shown at the top of this page, a Yubikey is a small USB device. (It comes in other styles as well.) It contains a chip which in turn contains cryptographic information unique to that key. Think of it as a serial number for the key.

You “associate” the key with an online account when you set up two-factor. That means inserting the key and usually pressing a button on it when asked. That causes the serial number to be registered with the online account.

Authentication

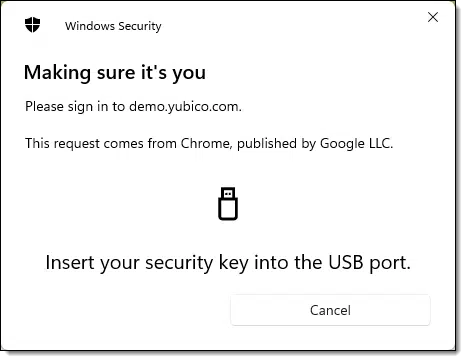

When two-factor authentication is later required, you’ll be asked to insert your hardware key into a USB port. (Some may also word wirelessly.)

You may then also be asked to touch a button on the key. Other security keys may use Bluetooth, NFC1, or other mechanisms to provide their information when requested.

After doing so, assuming it’s the correct security key previously associated with your online account, you’ll have passed two-factor authentication.

Thereafter, as with most two-factor authentication mechanisms, you’ll likely no longer need to provide the additional authentication until you move to a different machine, use a different browser, or clear your browser’s cookies.

That’s hardware key security in a nutshell.

How it works

YubiCo has a page describing the process.

To summarize: when you use a YubiKey, it acts as a virtual keyboard and “types” in the authentication code.2

ccccccgdrcngvihelvrukkkukljkvvvhifcifvuuvedb

That’s a code from an old YubiKey I no longer use. It has two parts: the device ID (which I’ve bolded above), aka the “serial number” I referred to, followed by a unique passcode. The passcode changes every time you use the YubiKey. Here’s the next from my device:

ccccccgdrcngbitejkdftrbietblcrlnhruilcdrrnch

Each code can be used only once.

The passcode is a number constructed from several pieces of information, including a timecode, a random number, a use count, and more. Most importantly, this is then encrypted before being displayed. Thus in the information above, the “bitejkdftrbietblcrlnhruilcdrrnch” portion of what’s been entered represents encrypted data.

When presented to the online service requesting the authentication, that service reaches out to the YubiKey servers, which have the decryption key to decrypt and confirm the identity of the specific YubiKey used.

How it’s more secure

Unlike other forms of two-factor authentication, a YubiKey is a physical device. You must literally present the device in order to authenticate.

Other forms of two-factor can be used from different devices, or in some cases intercepted and captured. That’s not possible with a hardware key. The key, and only the correct key, must be physically present to work.

Of course, with greater security comes a different form of risk: losing the key.

Losing your second factor

If you lose your hardware key or the key is somehow damaged, it would seem that you’re now locked out of your account. Fortunately, in practice that doesn’t happen.

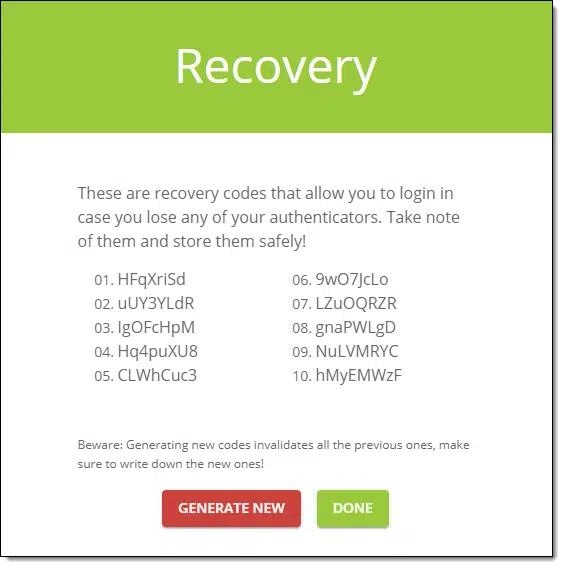

When you set up two-factor authentication — any two-factor authentication — the service you’re setting it up with should also have you set up a recovery mechanism for just this situation. Typically it’s a series of codes that can be used in place of your second factor.3

What’s important is that you:

- Get the codes to begin with.

- Keep them in a safe/secure place you can access if you ever need them.

Typically each code can be used only once, but you can generate a new set of codes after you’ve successfully signed in. You would also disassociate your lost second factor from the account and hopefully set up its replacement.

Multiple two-factor

Another approach to protecting yourself from authenticator loss is to have more than one, if your online service supports it. That means you could:

- Have two YubiKeys associated with the same account (if supported), keeping the second in a safe location in case the first is lost.

- Enable Google-Authenticator compatible two-factor authentication in addition to YubiKey.

- Enable email or SMS two-factor in addition to YubiKey.

With the exception of the first, however, by making the other approaches possible, you’re kind of side-stepping the extra security provided by the hardware key.

Do this

Use two-factor authentication.

Use a YubiKey if you like, particularly if the account you’re securing warrants an extra-tight level of security. Most people don’t need this, and other forms of two-factor will do quite nicely.

While you’re here, if you found this article interesting, please subscribe to Confident Computing! Less frustration and more confidence, solutions, answers, and tips in your inbox every week.

Podcast audio

Footnotes & References

1: NFC is Near Field Communication, a technology used to transfer data over short distances. NFC is based on the technology called RFID, also known as Radio Frequency Identification.

2: Literally. I just positioned my cursor in this document as I was writing it and pressed the button on my YubiKey to “type” what you see.

3: Other secure forms of recovery information are often used as well, including alternate email addresses, SMS messages, and more. Recovery codes are perhaps the safest, as they’re not associated with email addresses or phone numbers that sometimes fall out of date.

Yubico, the manufacturer of Yubikey, also has an authenticator app available for desktop and Android phones which works the same as the Google and Microsoft authenticators, providing hardware encryption nearly everywhere.

Instead of using the QR code on a website to link an authenticator app, there’s usually an alphanumeric code just below it. Copy that code into the Yubico Authenticator app (I also have a text file with the codes as a backup.)

When asked to provide an authenticator code when logging into a website, I open the Yubico Authenticator app, select the website I’m logging into, touch the Yubikey when prompted, and the code is generated and copied to the clipboard for pasting into website.

The app works with a single Yubikey, which is when my text file comes into play. I can then take a second Yubikey, open the Yubico Authenticator app, and copy the codes from the text file into the app, giving me two keys or more to use.

Two of my Yubikeys are NFC capable and work with my phone. And I do have several spare keys in case one goes missing.

This is a very interesting article. Thank you Leo for constantly coming up with things I did not know I needed to know about.

Does this device work with all websites that offer two-factor? If not, is there a way to find out without contacting all the websites individually?

Have you heard of these devices being cloned by bad guys, who then successfully get into accounts belonging to others?

Each website needs to support it. I know of no absolutely canonical list, but YubiKey does have this list: https://www.yubico.com/works-with-yubikey/catalog/?sort=popular

Nope, haven’t heard of any instances of compromise.

Been using Yubikey for about 3 years. You cannot clone or copy the contents of a Yubikey to a second key. You must register each key with every site separately. A bit of a pain but worth the trouble. I have a USB-A and USB-C, (both NFC so my android phones can read them and I use them with the Yubico Authenticator app). If you wait they often run a nice Black Friday sale after Thanskgiving and I combined it with a another discount to get 2 keys for about $70 bucks.

Also, there is a limit of 32 “accounts” you can configure on a single key. Given that some sites don;t allow for a key, it would be difficult to run out of space (I use 16 of 32 on my keys). Also, the small brass touch point on the key is NOT, I repeat NOT, a fingerprint reader – it merely acknowledges a person is touching the key (completing a circuit) to validate and generate a code.

You link to the following Yubikey page :

https://developers.yubico.com/OTP/OTPs_Explained.html

So it seems you use your Yubikey in OTP mode, which is the equivalent of using phone-based 2FA with a TOTP application (but through a hardware device) ; not the U2F mode, which is what is usually meant by hardware key-based 2FA ; which is the safest 2FA mode.

https://developers.yubico.com/U2F

Is that correct ?

I bought 2 yubikeys about a year ago. So far, it works with one site that I use. My password manager has dozens of accounts that do not work with yubikeys. I am ready if the world ever improves.

Might be more use to a Google, Facebook, Twitter, Cryptocurrency type of person.