An example of a larger problem.

One of my more popular YouTube videos is entitled “What’s the Best Long Term Storage Media? Tips to Avoid Losing Data in Your Lifetime“. In it, I argue that there is no such thing as “best” and the appropriate approach is to periodically copy the data you want to preserve to newer technologies.

It was posted a couple of years ago, and still receives a steady stream of comments and opinions. If you’re at all interested in how I recommend you plan for truly long term storage, I recommend you watch it, or read it’s companion Ask Leo! article here.

This article is a bit of a crossover between tech and philosophy and critical thinking. I’m going to address one of the surprisingly common comments I get on the video regarding the longevity of stone tablets, and how that exposes common flaws in how we evaluate information.

Stone tablet longevity

People sometimes mention stone tablets as being a reliable storage mechanism for data from previous millennia. This is incomplete thinking and shows what’s known as survivorship bias. It’s important to recognize so as to draw more accurate conclusions and make more correct decisions.

Stone tablets?

No one is suggesting you use stone tablets to store data. Again, if you’re interested in my thoughts on long term storage, watch that video, or read the article.

This is about how a common comment exposes a common fallacy causing us to arrive at incorrect conclusions. The common comment is that stone tables are still around from millennia ago, and thus they represent a viable form of long-term data storage.

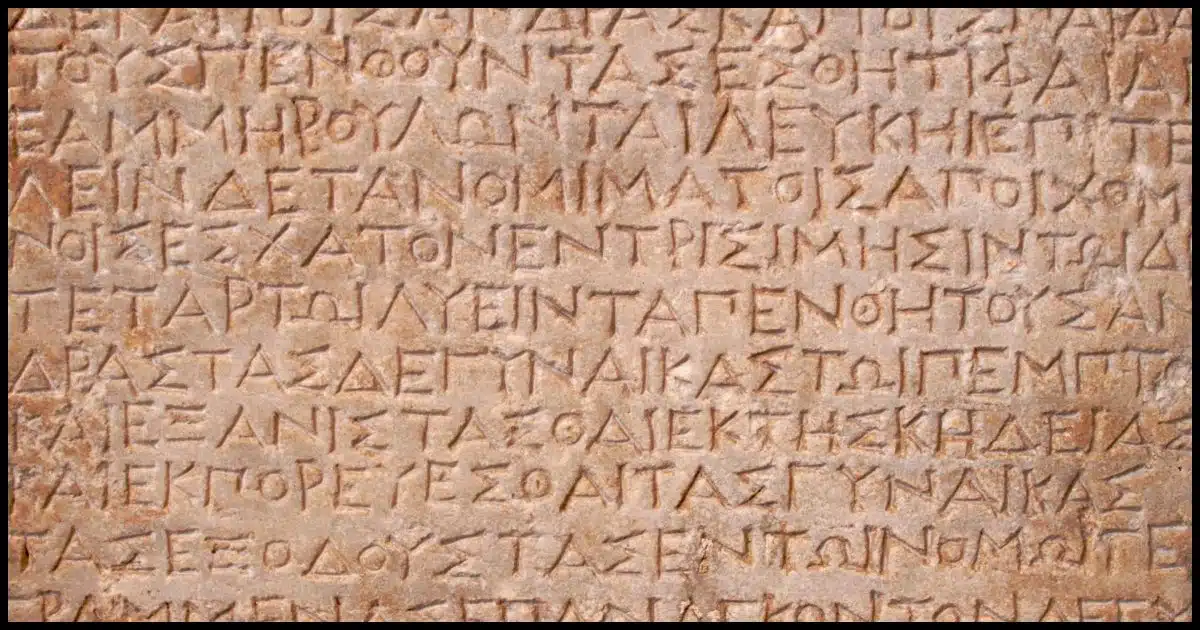

There’s no arguing that stone and clay tablets from a few thousand years ago have preserved an incredible amount of fascinating information about those times. While they’re certainly more resilient than other ancient technologies — such as papyrus scrolls, for example — they’re certainly not a storage mechanism that compares well with the majority of today’s technologies.

Tablets we know of represent only a small percentage of the number of tablets originally created. They represent the survivors, the ones that made it. Put another way, the majority of information “stored” on stone has been lost. I expect the percentage of tablets that survive is a small fragment1 of those created. But even if fully half of all tablets made were to still exist, that represents 50% data loss –not something we would consider acceptable today.

That people keep suggesting this, however, is evidence of a larger problem that transcends storage and even technology.

That larger problem is incomplete thinking and bias.

Help keep it going by becoming a Patron.

Survivorship bias

Misinterpreting a smaller number of survivors as representative of a greater whole is a form of something known as survivorship bias.2

An example of this type of bias is folks who say “We grew up without bicycle helmets, and we did just fine!”, which ignores all those injured or killed because they weren’t wearing helmets. That is drawing a conclusion based on a small number of datapoints that are then applied broadly. That helmets save lives only becomes evident when you examine all the data, including the injuries and fatalities, and not just your own localized experience of having survived unscathed.

The Wikipedia article on the topic includes another great example from World War II of how understanding survivorship bias at that time saved lives.

Some stone tablets created thousands of years ago remain today. But that doesn’t imply that all, or even most, of the tablets created then did. Some people ride bikes without brain injury, but not all do. Taking a small sample of “survivors” as representative of something larger results in drawing the wrong conclusion.

Partial data

Stone tablets are good examples of other related issues of incomplete thinking.

Many, if not most, of those tablets are only partial, broken, pieces of larger stones. Thus while it appears we have a tablet containing something that survived, we may find it’s unintelligible because of what’s been lost.

Think of it as losing a portion of an important digital file. Even the surviving data might be useless if that missing data was critical.

It’s more than understanding that you’re looking at only the survivors; the actual quality of those survivors needs to be considered as well. If half of the surviving tables are only partial, then that’s another 50% data loss on top of what we discussed above. (I expect the actual number of partial tablets to be significantly higher, and thus the data loss as well.)

File formats

One of the common and quite correct observations with long-term data storage is that of file formats. For example, there are many files created only a few decades ago for which there are no working programs. While the data could be reinterpreted and new software developed, it’s costly and in many cases not justifiable.

Our stone tablets have a version of the same problem. Many are written in languages that are simply not used any more, and even forgotten.

That doesn’t mean they can’t be re-interpreted and translated, but once again, that takes time and effort. (One entire and interesting research project3 is applying AI technology to translating ancient cuneiform tablet fragments.)

This implies then, that before drawing conclusions, we need to:

- Understand whether we’re basing our ideas on all the data, or just the survivors. What data is missing, and how might it affect our conclusions?

- Understand whether survivors really are survivors, or if they’re damaged and incomplete so as not to truly live up to the characterization.

- Understand whether survivors are things we can even understand, and if not, whether we’d consider that survivorship at all.

Failure bias

A related type of faulty thinking that I see frequently is what I’ll refer to as “failure bias”. It’s kind of the opposite of survivorship bias.

If it happened to me, it’s happening to everyone.

For example I’ll get a complaint — often quite passionate — about some feature of Windows or other software that isn’t working as an individual expects. They jump to the conclusion that “everyone” experiences the same failure, and “everyone” feels the same way.

That’s rarely the case. Again, it’s a result of not thinking through the issue, which is quite easy to do when frustrated.

Do this

First, keep rolling your important data forward to new technologies periodically, and of course, keep duplicate (backup) copies as well. This will ensure your data’s storage is refreshed on currently accessible media. There is no “best” media. The solution is a process of periodic migration.

But the real takeaway here is to really understand the data you’re looking at — and the data that’s missing — before jumping to conclusions. Survivorship bias, as I’ve discussed above, can have many different aspects depending on the situation. While claiming that stone tablets might be a long-lived storage media is somewhat impractical and hopefully facetious, that it’s a common conclusion shows just how incompletely many people think about the issues at hand.

And this applies to so much more than just a theoretical argument about data storage.

For more tips and hopefully less bias, subscribe to Confident Computing! Less frustration and more confidence, solutions, answers, and tips in your inbox every week.

Podcast audio

Footnotes & References

1: No pun intended. Honest.

2: Survivorship bias – Wikipedia

3: Groundbreaking AI project translates 5,000-year-old cuneiform at push of a button.

I still have some files I created in the 80s by copying the data to hard drives, CD, and DVDs. Only a small portion survived, a conscious decision to delete useless files. Now, I wish I had copied over a few more for nostalgic purposes. I also scanned all my parents and my photos and keep them preserved by copying them over to my new devices. There’s always enough overlap of technologies to be able to keep this up.

Great article, thanks